Strong Teeth, Fresh Breath, Brighter You.

Beyond the Smile: The Unspoken Risks and Realities of Dental Surgery

Language :

Topics:

The Silent Scrape: What Really Happens When the Drill Slips

You trust us with your smile. You sit in the chair, put on your sunglasses, and place your well-being in our hands. It’s a trust we dentists take more seriously than you can imagine. But behind the confident demeanor and the gentle reassurances, there’s a constant, low-grade hum of vigilance. We are navigating a microscopic landscape, millimeters from potential disaster.

Today, we’re pulling back the sterile curtain. We’re talking about the things we discuss in break rooms and at conferences, but rarely, if ever, with patients: perforations, common errors, and the haunting specter of failure.

The Unseen Perforation: When the Wall Gives Way

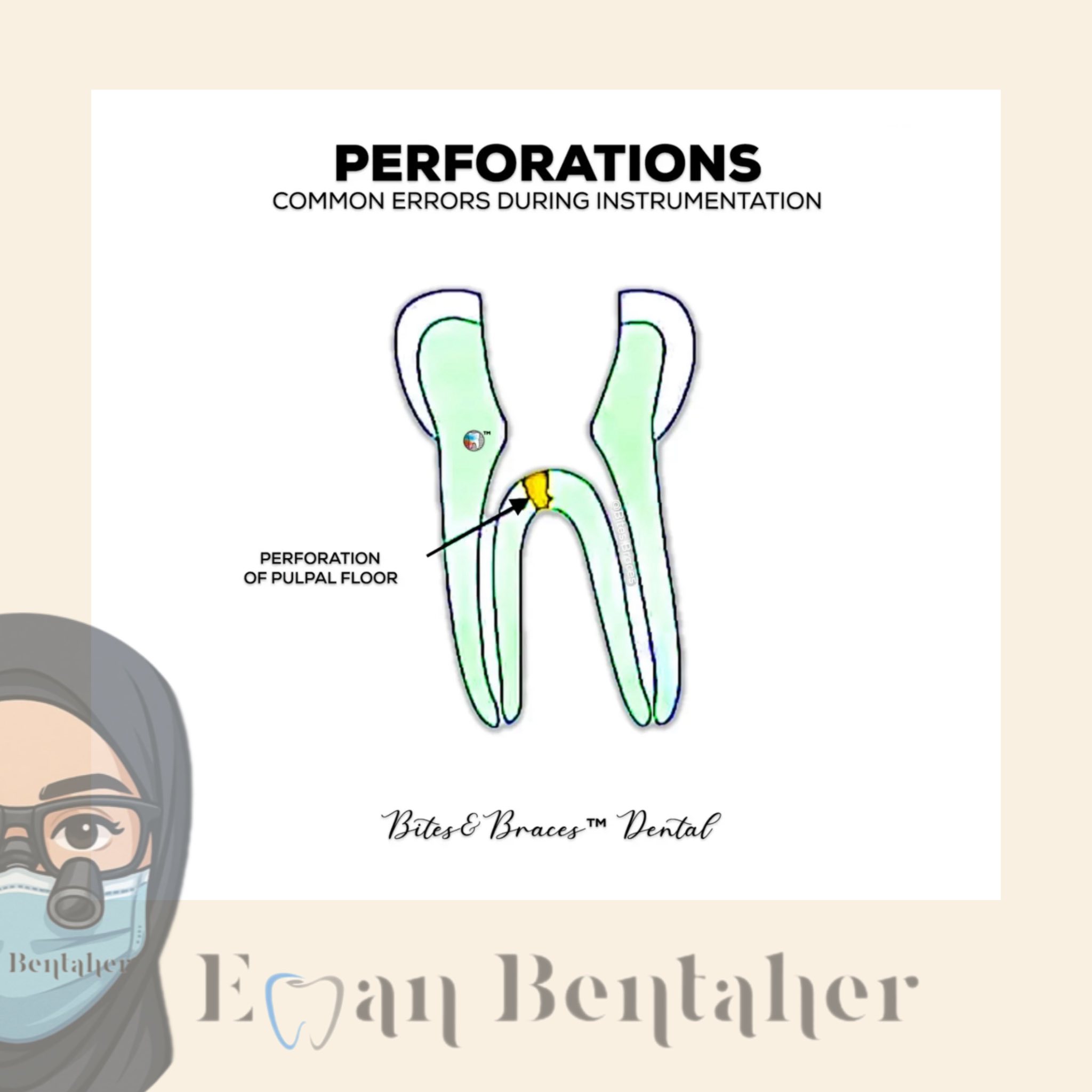

A perforation is exactly what it sounds like: an unintended hole. It’s when our instrument—a drill, a file, an implant drill—goes through the wall of a tooth or the bone where it shouldn’t.

Why is this a "failure" many dentists face? Because anatomy is a trickster.

-

The Root Canal Perforation: The inside of a root isn't a straight, wide highway. It's a complex, curved, and often calcified canal system. We're cleaning it blind, guided by feel and 2D X-rays. A moment of miscalculation, an overly aggressive file, or an unrecognized sharp curve can lead to a "strip perforation" or a "ledge" that becomes a perforation. This creates a new pathway for bacteria, jeopardizing the tooth's survival.

-

The Sinus Communication: The roots of your upper molars are often intimately close to, or even poking into, the maxillary sinus. Removing one of these teeth can sometimes create a small hole between your mouth and your sinus. Most are small and heal on their own, but a larger one, if missed or poorly managed, can lead to a chronic sinus infection that feels like it’s coming from your tooth.

-

The Implant Misadventure: Placing a dental implant is a surgery of precision. A misread CT scan, a slight deviation in the drill path, or poor bone quality can send the implant drilling into the nerve canal (causing permanent lip numbness) or out the side of the jawbone.

The Common Thread? It’s rarely about a lack of skill, and almost always about a lapse in judgment, inadequate planning, or an unpredictable anatomical variation.

The Orchestra of Errors: Common Instrumentation Slip-Ups

Perforations are the dramatic soloists in the orchestra of potential errors. Here are the other, more common instruments that can play out of tune:

-

The Ledged Canal: In a root canal, if the initial file doesn't follow the natural path of the canal, it can create a "ledge" or a false passage. All subsequent instruments will follow this false path, leaving the true canal untreated and infected.

-

Separated Instruments: This is every dentist's quiet nightmare. A tiny, flexible file used in root canals can fracture (separate) inside the tooth. We now have a piece of metal stuck in the very canal we're trying to clean. Retrieval is often complex, expensive, and not always successful.

-

Over-extension of Root Canal Material: The filling material used to seal the root canal can be pushed past the tip of the root. A little bit is often tolerable, but a large amount can cause persistent inflammation and delayed healing.

-

The High Filling: It seems simple, but a filling or crown that is just a fraction of a millimeter too high can throw off your entire bite, leading to jaw pain, headaches, and a tooth that feels traumatized with every chew.

The Secret Surgeons' Club: What We Don't Say At The Chair

This is the hidden curriculum of dentistry. The things we only whisper about.

-

"The Tooth is a Goner": Sometimes, from the moment we see the X-ray or start the procedure, we know the tooth is not savable. The decay is too deep, the fracture goes too far, the infection is too severe. But we don't say, "This is hopeless." We say, "It's a challenging case, but we'll do our best." Why? Because we must try, and because hope is a powerful part of healing. We never want a patient to feel we gave up on them.

-

"I'm Working Blind Here": Even with the best technology, a lot of dentistry is done by tactile feel. We can't see the bottom of a cavity or the tip of a root file. We're relying on training, experience, and a mental 3D map. This inherent uncertainty is a constant, silent companion.

-

"My Heart was Pounding": When a file separates or we see a bleeder we didn't expect, a cold wave of adrenaline washes over us. The mask hides our grimace. The calm voice is a practiced performance. Inside, we're running through every protocol, every possible solution, praying we can fix what just went wrong.

-

The Referral Gambit: When a general dentist refers you to a specialist (an endodontist for a root canal, a periodontist for gum surgery), it's not always because the case is complex. Sometimes, it's because they've hit a wall. They've ledged a canal, or they sense a perforation risk, and the ethical, professional thing to do is to hand it over to someone with a microscope and more advanced tools. This is not failure; it's wisdom.

A Note on the "Failed Surgeon"

It’s a harsh term, but it exists in our lexicon. The "failed surgeon" isn't necessarily one who lacks hand skills. Often, they are brilliant technicians. The failure is in one of three areas:

-

Case Selection: The inability to say "no." Taking on a case that is far beyond their skill level or the biological limits of what is possible.

-

Hubris: The refusal to ask for help, to refer, or to acknowledge a mistake when it happens. This "solo pilot" mentality can do the most damage.

-

Hands vs. Mind: Having the steadiest hands in the world is useless without the diagnostic acumen to know where to place them and the judgment to know when to stop.

The Path Forward: Trust Through Transparency

So, what does this mean for you, the patient?

-

Choose a Dentist Who Invests in Technology: A dentist who uses a CBCT scanner (a 3D X-ray) for complex cases is not just showing off. They are eliminating guesswork. They are mapping the anatomy to avoid these very errors.

-

Ask Questions: "What are the potential complications of this procedure?" A good dentist will be honest about the risks, including rare ones like perforations or separated instruments.

-

Understand That Perfection is a Journey: Dentistry is not an exact science. It's a art practiced in a biological environment that is constantly changing. Complications can happen to the very best clinicians.

-

Value Honesty Over Infallibility: If your dentist makes an error and is transparent about it, that is a sign of immense integrity. The cover-up is almost always worse than the initial mistake.

We enter this profession to heal and to help. The fear of "failure" is what drives us to be better, to study more, to invest in better tools, and to treat every single tooth with the focus and respect it deserves. By understanding the silent challenges we face, the trust between us can become even stronger.